This week we find ourselves deep in Gothic Dublin with Brian J. Showers.

When I moved to Dublin in 2000, I immediately set about familiarising myself with the literary heritage of my new home. Of course having a lifelong interest in ghost stories and things that go bump in the night—which, by the way, shows no sign of abating—my attention naturally focused on Irish contributions to the genre. This curiosity resulted in my first book, Literary Walking Tours of Gothic Dublin (2006), copies of which are still floating about if you’ve the mind; and a twice-yearly journal I edit called The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature (2013- ). The title pretty much says it all.

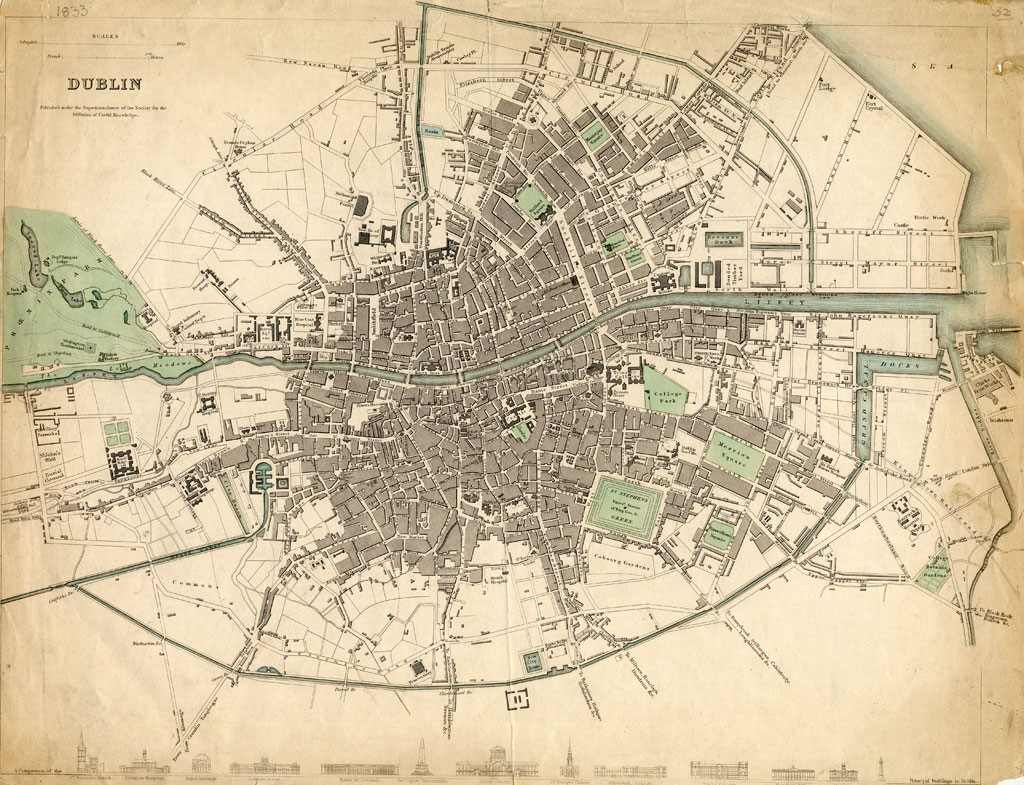

Sure, I’d read Wilde and Stoker and Dunsany before moving to Dublin, but never with the added opportunity for geographical context. Being able to walk the same streets, the same paths and lanes, is a far more illuminating experience than sitting in the Midwest with a European city plan. Now that I was in Dublin I could visit Wilde’s birthplace on Westland Row, the church where Stoker married shortly before moving to London, the hospital on Jervis Street where Lord Dunsany lay wounded from shrapnel during the 1916 Easter Rising. I could walk from Charles Maturin’s house on York Street, where he wrote Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), to nearby Saint Peter’s Church, where he served out his final days as a curate. Maturin was eventually buried in the churchyard there, until the church, the yard, and hopefully the deceased too were cleared away to make room for a YMCA. But still, that plot of land, that precise location along the street, will always hold, like geological layers, a cumulative spatial significance. At least for me.

That’s the thing about Dublin or, I would imagine, any city of substantial size: Time collapses on itself, compressing layers of place, both literal and figurative, one on top of the other. There is the surface of the modern day, yes, but if you learn the city’s furtive language, you will also learn that a particular bend of a certain road echoes a now vanished waterway; or that behind the façades of certain ancient buildings on Aungier Street stand structures still older and forgotten. Secrets are concealed all over this town.

In October of 2000, while I was still searching for legitimate work, I found myself sitting in my new Dublin flat reading Bill McCormack’s biography of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the Victorian ghost story writer whose gothic novel Uncle Silas (1864) still has many sinister thrills to offer the modern reader. There is Le Fanu’s popular, if slightly sensational, vampire novella “Carmilla” (1871-2), which many already know. But my favourite tale is “Green Tea” (1869), a horrific depiction of a man’s psychological decay, originally published in All the Year Round by Charles Dickens before it was later collected in Le Fanu’s crowning achievement In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Anyway, that autumn afternoon, as I was sat in my armchair reading, I turned to a page showing a photograph Le Fanu’s tombstone, with a note that he was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin. It was an epiphany, albeit maybe an obvious one: We’re not in Wisconsin anymore. Why continue sitting in the chair? Not content to just read about these places, I could now visit them too! I jumped up, grabbed a map and my coat, and within minutes was heading west towards Harold’s Cross—a short fifteen-minute walk from my flat.

Mount Jerome Cemetery is Dublin’s “other cemetery”—by that I mean it is not Glasnevin Cemetery on the north side of the city, which, due to its high volume of political heroes, is plainly the more celebrated of the two. However, for the lover of fantastical literature, Mount Jerome may well have more to offer. Mount Jerome was founded in 1836, originally a Protestant cemetery, an overflow for the dangerously brimming city graveyards. With cholera epidemics sweeping across Ireland at the time, a bit more space was necessary. By the 1990s, the cemetery had fallen into extreme disrepair. It was overgrown with weeds and the quantity of empty beer cans threatened to outnumber those interred there. Roots had overturned tombstones and advanced deterioration worked on some of the burial ground’s grander monuments. Fortunately, the cemetery was restored by the Massey Brothers at the turn of the century. While there is still a sense of majestic decay—proper to any such cemetery of nineteenth-century vintage—I cannot think of a more pleasant way to spend an afternoon, provided the weather holds: ambling among the tombs and reading the details of lives etched into the stones.

As I mentioned already, the vault of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873) is, in my opinion, Mount Jerome’s literary centrepiece. The vault is topped by a large capstone facing the open sky. The elements have nearly erased all names of those interred therein, though traces of Le Fanu’s name can still be discerned in the limestone if the sun is at the right angle. His gothic novels and ghost stories were much admired by M. R. James, among others, and echoes of his writing can be found in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and—I’m fairly certain—Family Guy. For the bicentenary of Le Fanu’s birth in 2014, I organised the vault’s restoration. With contributions from members of the Le Fanu family, we had the stone scrubbed clean of grime and lichen, and a new plaque installed, which reads: “Here lies / Dublin’s Invisible Prince / Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu / 28th Aug. 1814 – 7th Feb. 1873 / Novelist and Writer of Ghost Stories”.

Not far from Le Fanu’s vault is the burial place of one of the most obscure Dublin writers: Oliver Sherry. Sherry was the nom de plume of George Edmund Lobo (1894-1971), which is how he is identified on the stone slab marking his simple grave. Lobo penned five slim volumes of poetry, but is now best remembered for (if that phrase is applicable to someone so thoroughly forgotten) an occult thriller entitled Mandrake (1929). With an introduction by the late genre scholar Richard Dalby, Mandrake was republished for the first time in eighty years by Medusa Press: “The story centers around the investigations of an American occult detective, Tom Annesley in two remote English villages. This area is terrorized by the immortal Baron Habdymos, malevolent sorcerer and last surviving of seven ancient adepts of black magic, and his evil bestial familiar or ‘mandrake’, which feeds on blood—a memorable creation worthy of M. R. James at his darkest.”

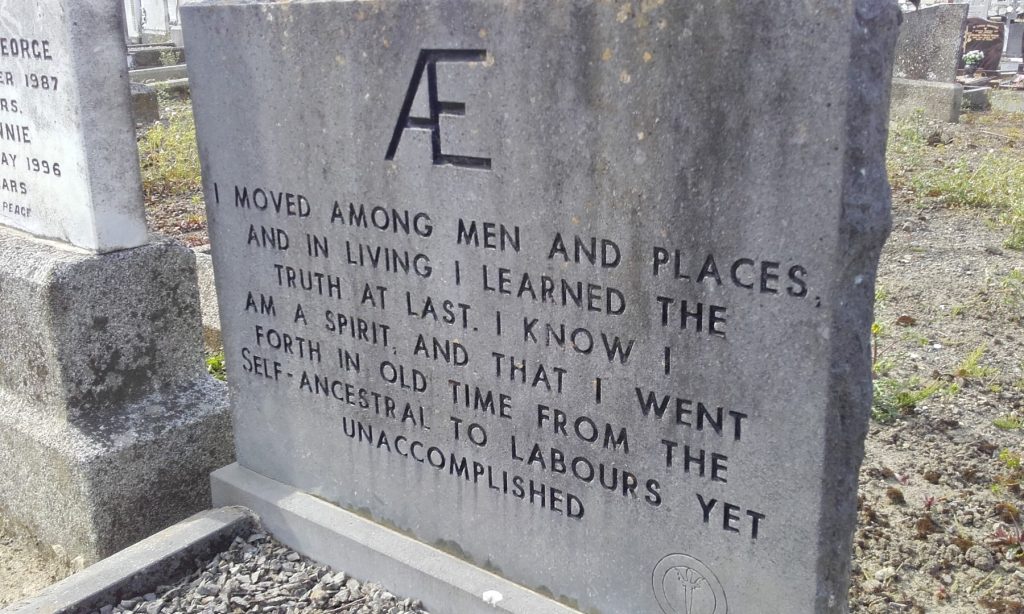

Next up is the resting place of George William Russell (1867-1935), who wrote and painted under the name A.E. I hesitate to call “A.E.” a pen name inasmuch as the name was the true spiritual manifestation of Ireland’s foremost mystic. A.E. outlined his beliefs in The Candle of Vision (1918) and Song and its Fountains (1933). In the latter he wrote: “I lay on the hill of Kilmasheogue and Earth revealed itself to me as a living being, and rock and clay were made transparent, so that I saw lovelier and lordlier beings than I had known before, and was made partner in memory of mighty things, happenings in ages long sunken behind time.” Occasionally A.E.’s works are on display at the Hugh Lane Gallery, including his sublime painting The Winged Horse; and a bust of his great bearded visage, sculpted by Oliver Sheppard, stands in the National Gallery—though for some reason they’ve none of his pictures on show there. On the poet’s headstone, beneath a deeply carved “Æ”, are the words: “I moved among men and places, and in living I learned the truth at last. I know I am a spirit and that I went forth in old time from the self-ancestral to labours yet unaccomplished.” Swan River Press re-printed A.E.’s Selected Poems for his sesquicentenary in 2017. It is currently his only work in print.

Just outside the cemetery’s chapel is the grave of Sir William Wilde (1815-1876), father of Oscar Wilde. While not directly a genre writer—Sir William was, in fact, an ear, nose, and throat doctor—his interests as an antiquarian and folklorist put him squarely in our literary purview with books such as Irish Popular Superstitions (1852) and Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira, Tenerife, and along the shores of the Mediterranean (1840). Sir William brought back from this Mediterranean tour numerous archaeological souvenirs, including a mummy, which he displayed his home on Merrion Square. (He also once had possession of Jonathan Swift’s skull, but that’s another story.) The Wilde’s home was host to a social circle that included the young Bram Stoker, and Sir William’s Egyptological reminiscences may well have played a formative role in Stoker’s novel The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903). Wilde’s gleaming white monument in Mount Jerome, flanked by fragrant lavender, also serves as a memorial to his son Oscar and his wife, the poet Lady Jane Wilde, who published under the name “Speranza”.

Further along from the cemetery offices, and behind a low hedge, is the grave of Christine and Edward Longford (1900-1980; 1902-1961). Edward was the chairman of the Gate Theatre and, with his wife, co-managed Longford Productions. So what brings us to their graveside? Both Christine and Edward seem to have had a particular affinity for our friend Le Fanu. They adapted no fewer than four of his stories for the stage: Carmilla (1932), The Watcher (1942), The Avenger (1943; based on “Ultor de Lacy”), and Uncle Silas (1947). Scripts for Carmilla and Uncle Silas are still extant; the other two have not yet shown up in the archives at Tullynally Castle. But perhaps a revival of Carmilla is soon due? Christine also wrote an introduction to Uncle Silas for Penguin’s abridged edition in 1940. I wonder if they knew they would be buried so close to him? Flecks of scarlet paint are still in the Longfords’ engraved names, while the dramatic masks of tragedy and comedy have been cut into the stone’s sides.

The final stop on our perambulation of Mount Jerome is the grave of Sir William Thornley Stoker (1845-1912). Thornley, the name he went by in life, was a surgeon like many other members of his family. He lived in a grand house on Ely Place, collected antiques, and served as president of the Royal College of Surgeons on Saint Stephen’s Green—there’s a portrait of him that still hangs there, though you might have to bluff your way in to see it. While he was writing Dracula, Bram contact his brother Thornley to consult him on the effects of head wounds. Thornley wrote a memo, even providing a diagram, showing where on the head certain blows might cause paralysis to the legs, arms, and face, and what medical procedures might be necessary in the wake of such a ghastly trauma. Bram incorporated Thornley’s notes into Chapter 21 of his magnum opus—describing Renfield’s unfortunate accident with some suspicious-looking mist that had gathered outside his cell window.

There is much else to discover in Mount Jerome, but the above names are some of my own favourite people to visit. The cemetery is not too far outside of Dublin, a forty-five minute walk from the city centre, an even shorter bus journey. One could easily spend hours among the stone urns, broken columns, stoic angels, and various memento mori that decorate the myriad vaults and tombs. I will, however, give one piece of advice: make sure you get an early start. There are signs at Mount Jerome’s entrance proclaiming that they close the front gates at four o’clock sharp. I would imagine they do mean business. I admit, I would not care to find out.

With thanks to David J. Skal for the use of his photos of the Wilde and Stoker graves; photo of Brian J. Showers by Aoife Herrity.

Brian J. Showers is originally from Madison, Wisconsin. He has written short stories, articles and reviews for magazines such as Rue Morgue, Ghosts & Scholars, and Wormwood. His short story collection, The Bleeding Horse, won the Children of the Night Award in 2008. He is also the author of Literary Walking Tours of Gothic Dublin and Old Albert, the co-editor of the Stoker Award-nominated Reflections in a Glass Darkly, and the editor of The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. He also runs Swan River Press, who can be found on

Brian J. Showers is originally from Madison, Wisconsin. He has written short stories, articles and reviews for magazines such as Rue Morgue, Ghosts & Scholars, and Wormwood. His short story collection, The Bleeding Horse, won the Children of the Night Award in 2008. He is also the author of Literary Walking Tours of Gothic Dublin and Old Albert, the co-editor of the Stoker Award-nominated Reflections in a Glass Darkly, and the editor of The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. He also runs Swan River Press, who can be found on ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.