Once upon a time…

By Pádraig Ó Méalóid

Once upon a time we would have written ‘Once upon a time’ as ONCEUPONATIME. But, because Ireland was never invaded by the Romans, we invented the space between words instead. And copyright. Sort of.

This is not as crazy as it sounds.

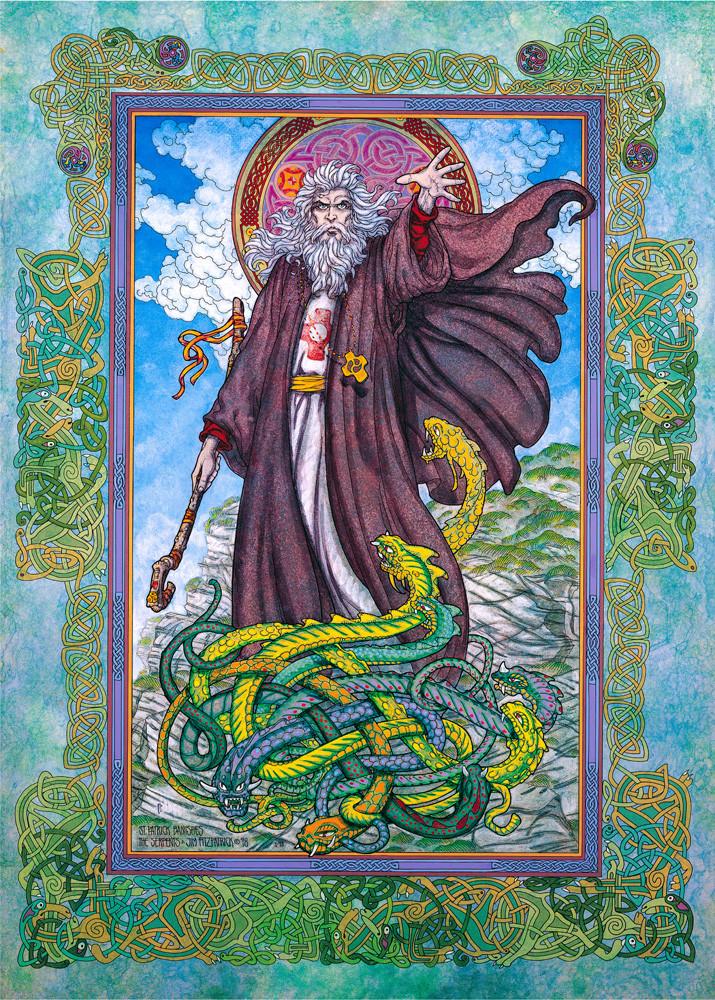

Christianity first reached Ireland in and around the year 400 AD ˗ predating Saint Patrick, the primary patron saint of Ireland (along with Saint Brigit of Kildare and Saint Colmcille – of who more later), who is wrongly credited with bringing the one true faith over here. The timing of this would have very closely coincided with end of direct Roman rule in Britain, that large island directly to our east.

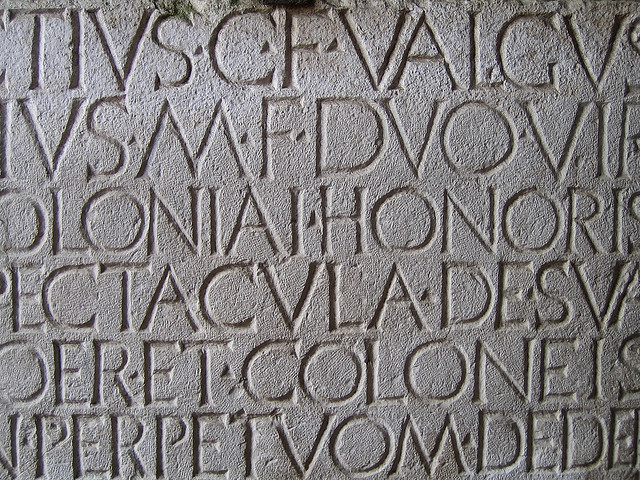

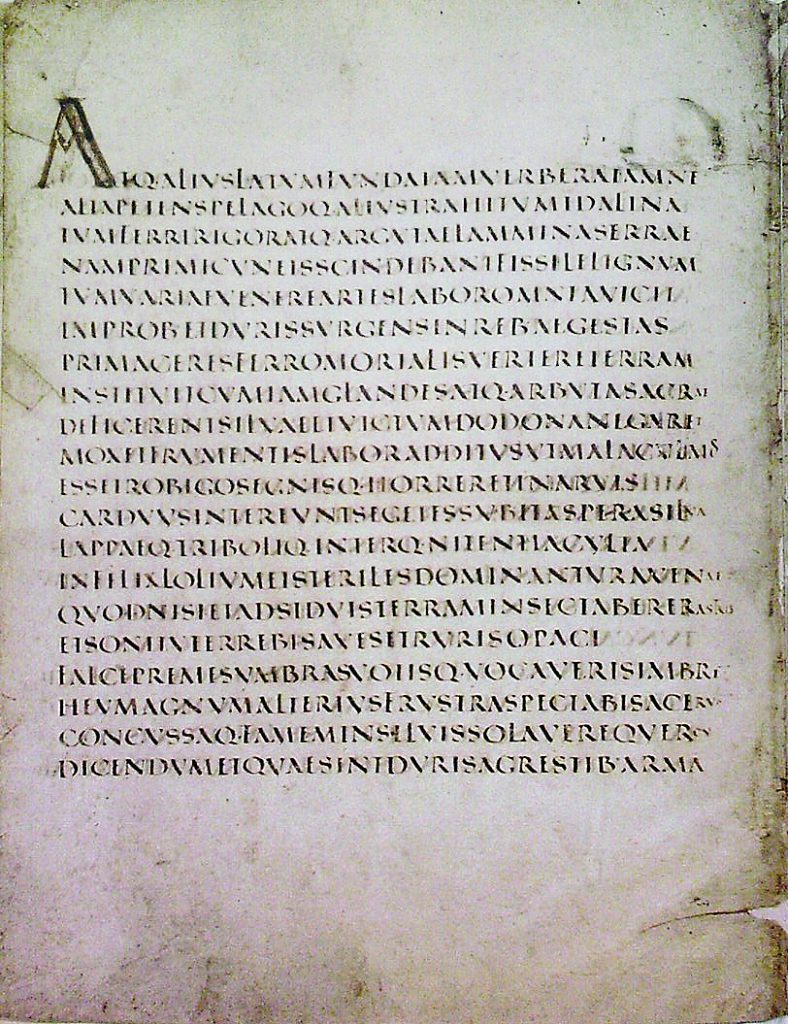

Although Greek had been the language of the first Popes, Latin became the language of Christianity between the first and third centuries AD, as the religion spread throughout the Roman Empire. And, whilst Classical Latin had used a vertically centred dot, known as an interpunct (or, as they would have written it, an INTERPVNCTVS) to separate words, this had died out by the end of the second century AD. Latin thereafter was written in a style known as Scripta Continua,

meaning Continuous Script, as demonstrated in the first line, above. (More correctly, of course, that would be SCRIPTACONTINUA…)

A large part of the reason for this is that Latin text was written, not for private reading, but as an aide-mémoire. When documents like the Bible were spoken aloud in public, the person speaking already knew the work off by heart, and only needed the physical document as a support. This was, as far as it went, an excellent idea, if Latin was your spoken language, and you knew what it was all meant to sound like. But this all fell apart when the desire to have a prompting text clashed with the fact that that prompting text was in a language you’d never used as your lingua franca, nor probably even heard spoken by a native, and you didn’t know where the words started or stopped.

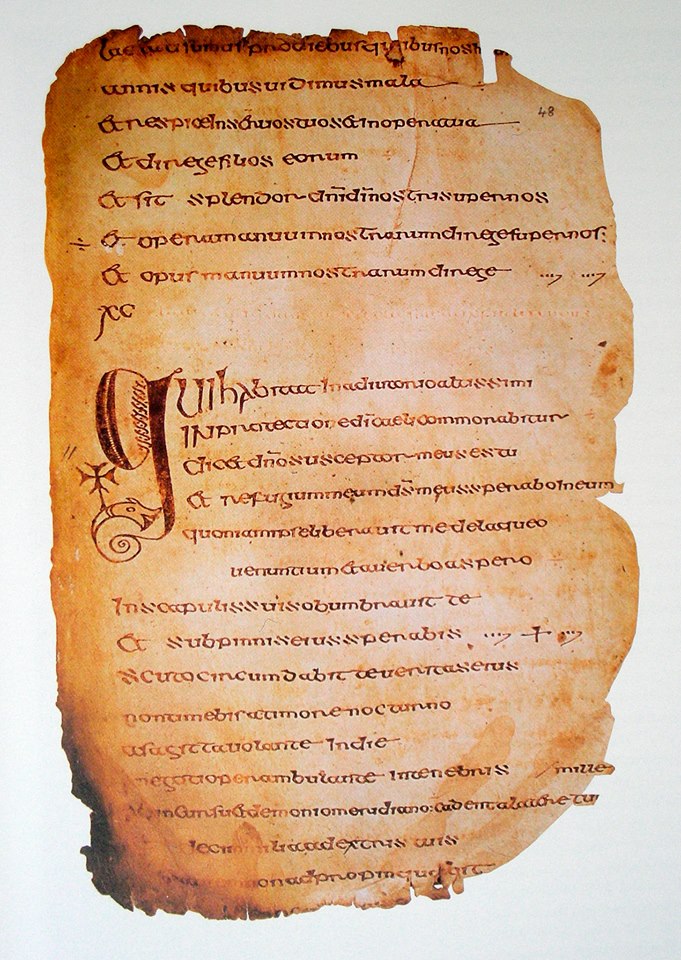

This is exactly what happened in Ireland. Whereas Christianity took hold here with great rapidity, leading to the founding of numerous monasteries, it came without the Roman occupation that went with it in pretty much all of the rest of Europe. And, along with that, the speaking of Latin started receding at almost exactly the same time. So, to help the better understanding of their sacred texts, in about the seventh century an unnamed Irish monk inserted spaces between those words. As Shane Angland says on his excellent ANGLANDICUS blog,

As Ireland was never part of the Roman Empire, Latin was a foreign language to the Irish. Their desire to learn and master Latin was driven by primarily theological and pastoral motives. Latin was the language of the western church, in her liturgy, theology, creeds, and scripture. The public reading of scripture in the early Irish church was an important part of theological training and also for the spiritual life of a monastic community.

Angland also quotes this from American librarian Frederick G. Kilgour’s The Evolution of the Book (OUP, 1998),

For the Irish monk who did not have Latin as a native tongue and was not intimately familiar with its varying forms of declension, conjugation, and inflection, reading an unbroken string of Latin words out loud to others was a formidable task. To facilitate oral reading the Irish scribes used space between words to make them more readily visible. Irish monasteries introduced word separation to continental monasteries, but it was not until the eleventh century that the practice was generally accepted on the continent.

The practice didn’t spread to continental Europe until some centuries later, however, because the decline of the Western Roman Empire resulted in, more or less, the historic period popularly known as the Dark Ages. While literary and cultural output in Northwestern Europe diminished, Ireland was sending out missionary monks to, and establishing monasteries in, Great Britain and Continental Europe. In many ways the Irish became the saviours of European civilisation after the depredations of the Scythian Huns and Germanic tribes like the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and other forms of Goths – some of which are still with us today…

One of the big players in all of this was Saint Columba, also known as Saint Colmcille (but definitely not the same Saint as Saint Columbanus), who is regarded, as previously mentioned, as one of the three chief saints of Ireland. He founded several monasteries, including one on the Scottish island of Iona, one of the likely places for the creation of parts of the Book of Kells. But that’s not all he did.

When he was a younger man Columba studied under Saint Finnian of Movilla (not to be confused with Saint Finnian of Clonard, of course). Finnian had a copy of Vulgate Psalter of Saint Jerome, the first translation of the Old Testament Book of Psalms into Latin, and a very prestigious thing to own. Later on, in 560AD, when he had a monastery of his own, Columba borrowed Finnian’s psalter and one night – with the help a miraculous light, according to legend – quickly made a copy for himself, specifically against the wishes of Finnian. Finnian then complained to the High King of Ireland, Diarmait mac Cerbaill (known nowadays as Dermot the Gerbil). The King handed down a judgement that said ‘Le gach boin a boinin, le gach lebhur a leabrán,’ meaning ‘To every cow her calf, and to every book its booklet.’ This is the earliest known recorded historical case-law on copyright, and therefore hugely historically significant.

Unfortunately, historically significant though it is, there are a few problems inherent to it, at least from a modern copyright perspective. As far as our understanding of copyright goes the rights to the Vulgate would belong to Saint Jerome, not to Saint Finnian. And even then there was room for argument, because Jerome was only translating the work of earlier writers, probably dating to the fourth or fifth century BC. In fairness, they would have been out of copyright by the time Jerome got around to them, as indeed would his own work have been, by the time Columba got around to copying – by 560 Jerome had been dead for a hundred and twenty years… In the end, though, what they were arguing about was which of them would get to produce more copies, and sell them, rather than anything godlier.

Having said all that, I doubt the expiration of even Disneyesque lengths of copyright protection was what drove Columba, who didn’t like the Dermot the Gerbil’s decision, and refused to accept it. Instead he gathered his allies in the Uí Néill clan and went to war with the High King’s forces, and beat them, at that, at the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne in what is now Sligo. Traditionally, 3000 warriors were killed on one side, as opposed to only one casualty on the other. After a few more transgressions against the king, leading to at least one more battle, Columba went into exile, promising to convert as many souls to Christ as he had been responsible for the deaths of.

Columba’s copy of Finnian’s psalter is now in the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin, and its Cumdach, or decorated book shrine, is on permanent display in the National Museum of Ireland on Kildare Street, just beside the National Library.

(*There is one deliberate fabrication in this, but the rest is ethically obtained from highly reliable online sources…)

FURTHER READING:

More about spaces between words in Paul Saenger’s Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading

Thomas Cahill’s How the Irish Saved Civilisation