Where All the Big Lads Hang Out…

by Pádraig Ó Méalóid

It’s the middle of August 2019, and you’re in Dublin for Worldcon – a Stranger, if not in a Strange Land, at least in a strange city. A strange city with many secrets, which sometimes only the locals truly know about. You’ve heard all about our native literary giants – George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce, and Flann O’Brien, to name but three – but even they were only human, prey to the wants and needs that mortal flesh is heir to. It’s only natural that you’ll want to know where they would have gone, and where you could go, too. So let me introduce you to one of the hidden architectural gems of my native city: the beautiful public toilets in the National Library of Ireland.

But before that, a brief diversion: once upon a time there were several fine public conveniences in the centre of Dublin – one in O’Connell Street, underneath the central division, for instance, which was first closed down, then all its external trappings removed, before being finally dug up and even those remaining subterranean ruins done away with, as the street was redeveloped. There were something like seventy of these public rest-stations spread throughout the greater reaches of the metropolis, employing roughly four hundred people between them, at their height, so you were never far from one. And, at a time when few homes had their own indoor – or, sometimes, even outdoor – lavatorial plumbing, they were a great boon to the public in general, and not just the occasional wanderer caught short.

But it was necessary, having once found them, to know which was the right door to enter through, the right stair to descend, for there was one final mystery to penetrate: the Irish language. In the light of the Gaelic revival movement in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, and particularly following the increased insularity of the incoming Free State, there was an ongoing movement for de-anglicising Ireland, meaning that many signs and notices that once were in English were now in Irish. The only clue as to which was which relied on your knowing the difference between two otherwise unhelpful three-letter words – FIR and MNÁ. Not only that, but these signs were usually hand-rendered in an old Irish script, not all of whose letters were what you thought they were. Fir is, handily enough, the plural of Fear, a man (which is pronounced differently to how you’re pronouncing it in your head, although you got Fir right), but you’d be hard put to have figured out that Mná (just about my favourite word in Irish, by the way, simply for its sheer contrariness, and the beautiful sound it makes when spoken out loud) is the Irish for Bean, a woman (which, again, is pronounced differently to how you think)[1][2][3].

However, once upon a time it would only have been men’s conveniences that you would have found on the streets of Dublin, as well as elsewhere. All three authors mentioned above, all habitués of the National Library, were concerned, in one way or another, with the lack of public facilities for ladies. George Bernard Shaw caused considerable commotion in 1900 when, as a Vestryman for London’s St Pancras district, he had insisted that a women’s public lavatory should be built on Park Street in Camden Town. [4][5]

Flann O’Brien’s last written novel, The Hard Life [6], is set in the early years of the twentieth century and features, amongst other characters, a man called Mr Collopy – the half-uncle of the narrator, Finbarr – who spends most of his evenings in conversation with a German Jesuit priest called Father Kurt Fahrt [7], where they discuss a matter that they are both very concerned with, a social evil that needs addressing. Although their conversations continue throughout the novel, with considerable seriousness, it is only at the very end that, although they never mention the problem directly, and use only polite euphemisms and circumlocutions, that we find out that the matter they are campaigning for is that of providing public lavatories for the womenfolk of Dublin. [8]

James Joyce very briefly gets in on the act, too. In his 1922 modernist monsterpiece Ulysses, all set in Dublin during the 16th of June 1904, we find this in Episode 8, called Lestrygonians, as part of Leopold Bloom’s stream of consciousness:

He crossed under Tommy Moore’s roguish finger. They did right to put him up over a urinal: meeting of the waters. Ought to be places for women. Running into cakeshops. Settle my hat straight. There is not in this wide world a vallee. Great song of Julia Morkan’s. Kept her voice up to the very last. Pupil of Michael Balfe’s wasn’t she?

The reference here is to the Irish poet Thomas Moore, whose statue still stands on a triangular traffic island at the junction of Westmoreland Street and College Street. That island was also once home to the exterior trappings of another underground convenience, so long closed that even I don’t remember it open, but which definitely existed in 1904. [9][10]

Frank Hall’s useful intervention in the nineteen-seventies (see footnote [2]) came almost too late, though. Times had changed, belts were ordered to be tightened by self-important men with handmade Charvet shirts, and not a single one of those seventy conveniences remains open today. And Thomas Moore probably never got to see the inside of any of those conveniences, not even the one he stood guard over for all those years, as he died in 1852, before most of them were undertaken. And he would no longer have the chance to, now, as his own one had its hollow corpse disinterred, and its empty grave filled in, just within the last few years, as part of the seemingly eternal works to extend Dublin’s tram network from two lines, to two lines with-an-extra-bit-added-onto-one-of-them. Sic Transit Gloria Mundi, and so on.

But at least Moore’s finger more or less finally points us to our final destination, the same destination as Joyce’s Leopold Bloom was hurrying to on the day in 1904. The road brings us, by a circuitous vicus of recirculation [11], around the outside wall of Trinity College, back to where we began. Finally, we are once more on Kildare Street, back at the National Library of Ireland, founded in 1877, but only finally located in its beautiful late-Victorian home in 1890, designed by father-and-son architects Thomas Newenham Deane and Thomas Manly Deane, who also designed the National Museum of Ireland building opposite, almost-but-not-quite its mirror image across the courtyard of Leinster House.

Once through the door you are in a beautiful round entrance hall, with an intricately tiled floor featuring the repeated word Sapientia, Latin for Wisdom. Dark brown carved wood, pierced with several stained glass windows featuring the great thinkers of antiquity bring the light of incipient knowledge into the hall, and a porter stands opposite you, waiting to guide you on your way. Upstairs are the Reading Rooms. Other delights await off to you right. But first, almost hidden away down two sets of stairs leading downwards, you’ll find the most beautiful set of Victorian public lavatories in Dublin.

For once I shall hold my whisht, and let the pictures do the talking, and tell you more eloquently of the spaciousness, the lovely old tiling, the shiny copper piping, and the general sense of purpose, of the capernosity and function of the place, than my words alone could do.

When you have taken care of your immediate corporeal needs, and exulted in the sheer loveliness of it all, you may wish to go back upstairs, and descent a different stairway, to the Library’s permanent exhibition of the life of William Butler Yeats, a day’s work in itself, if you wanted to see it properly. Back upstairs, you might like to take a rest in Joly’s Café, oddly austere, like a Bauhaus-inspired works canteen, but none the worse for that. It is my favourite venue for meeting friends, as it’s almost invariably half-empty – I’ve shared tea there with Joyceans and Flannoraks, and with serious scholars of the history of Irish Science Fiction, and even with the chair of the Dublin Worldcon. [13]

When you have finally finished, at least for this time, your time in the National Library of Ireland, you can walk along Molesworth Street, past the Freemasons’ Hall, home to the Grand Lodge of Ireland, where legendary Irish Times editor RM Smyllie was once a member, you’ll eventually find yourself on Dawson Street where, if you stand outside Hodges Figgis, Ireland’s oldest bookshop, you’ll be able to catch the newly-extended Luas Green Line back along to O’Connell Street, and take the short connecting stroll to Abbey Street, where the Luas Green Line will bring you almost to the door of the Convention Centre, where Worldcon has been waiting for you.

Seo chuam mo thram! Slán go foil.

[1] Whilst Sean Bean may be an actor of some ability, over here sean bean is an old woman. And don’t even get me started on the difference in pronunciation and meaning between Seán, séan, and sean…

[2] Many years later Irish broadcaster Frank Hall – fondly recalled by a certain generation of Irish people for his 1970s satirical TV programme, Hall’s Pictorial Weekly – was to offer a useful mnemonic solution: Fellows In Residence for FIR and Men Not Allowed for MNÁ.

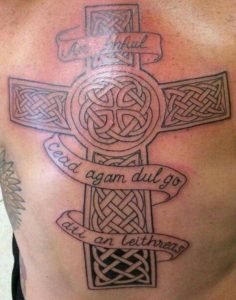

[3] There remains, deep in the Irish psyche, an almost mystical connection between the Irish language and public commodes. Perhaps because, despite being taught the language for many years in school, many people come away with barely a few words and phrases, the most commonly used, and most cherished being ‘An bhfuil cead agam dul go dtí an leithreas?’, meaning, quite simply ‘May I go to the toilet?’, a phrase many children were obliged to use, rather than its English equivalent. Indeed, in these Internet days the phrase has taken on a life of its own, with many online posts advising unwary foreigners that the expression is an ancient Irish blessing, or the equivalent of telling someone you love them truly, madly, and deeply. Whether the owner of this tattoo was aware or the phrase’s true meaning or not, and whether it was an unfortunate mistake or a possibly equally unfortunate moment of post-ironic humour, we do not know.

[4] Shaw gives at least his own version of the story in his essay The Unmentionable Case for Women’s Suffrage, published in The Englishwoman in March 1909, which didn’t necessarily agree with other versions from the time, including the minutes of meetings at which he raised the subject. Still, a man can be forgiven for making himself the hero of his own story, I suppose.

[5] Of course, it almost goes without saying that women’s organisations such as the Ladies Sanitary Association had been attempting to address the subject of the need for ladies’ loos for some time before that, without any apparent success, until the politicians, at that time all men, began to take notice.

[6] Whilst it is true to say that The Hard Life was the last novel Flann O’Brien wrote, it is perhaps more factually correct to say that it is the last book he wrote from beginning to end which was published in his lifetime. When he died, on April Fools’ Day in 1966, he was working on a book called Slattery’s Sago Saga, of which the kindest thing to say is that it may be as well it remained unfinished. There was another book that remained unpublished at that time, however. Flann’s second written novel – if we brush swiftly past both An Béal Bocht and Children of Destiny [6a] – was The Third Policeman, written in 1939 & 1940. This was rejected by Longmans when he submitted it to them, and the manuscript remained in various drawers in various pieces of furniture until after his death, which his wife Evelyn had it published, and it is now probably the book upon which his legacy will most firmly stand.

[6a] While still a student at University College Dublin Flann, then still largely known by his given name of Brian Nolan – was involved in a project with several of his co-students, including Niall Sheridan, Donagh McDonagh, Denis Devlin, and probably his own brother, Ciarán Ó Nualláin, as well – to create a book called Children of Destiny. He had previously announced that ‘The principles of the Industrial Revolution must be applied to literature. The time had come when books should be made, not written – and a “made” book had a better chance of becoming a best-seller’ This book was to be, according to Sheridan, ‘the precursor of a new literary movement, the first masterpiece of the Ready-Made or Reach-Me-Down School.’ [6b] They would write the book in different sections, then stick the pieces together in committee. The book was never completely – and possibly never even started – but its influence can be clearly seen in At Swim-Two-Birds, where the nameless narrator states that ‘The entire corpus of existing literature should be regarded as a limbo from which discerning authors could draw their characters as required, creating only when they failed to find a suitable existing puppet. The modern novel should be largely a work of reference.’

[6b] I cannot let the moment pass without noting the interesting correlation between Flann O’Brien, the idea of the Ready-Made novel, and the Readymades of France’s Marcel Duchamp, a few decades before, in particular his Fountain, a porcelain urinal placed on its side and signed R. Mutt. Much controversy surrounds the actual authorship of the work, with Duchamp himself writing to his sister that ‘One of my female friends, who had adopted the male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.’ He never identified his collaborator, but it is generally accepted that it was either Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven or Louise Norton. Make what you will, in this brief set of notes on the subject of men and ladies and toilets and artworks, and toilets as artworks, of a woman having created arguably the most influential artwork of the twentieth century, only to have the credit stolen by a man…

[7] The International Flann O’Brien Society presents two awards, the Father Kurt Fahrt, S.J. Memorial Prizes, at their biennial academic conferences. I was nominated for the award for a shorter piece, known as the Small Fahrt, in 2017 but, despite making it to the shortlist, did not win. Not that I’m bitter, of course…

[8] Flann was certainly a fan of Shaw’s work, having used a character name from Shaw’s science fictional five-play series, Back to Methuselah, for his very first literary pseudonym, Brother Barnabas, and made several other references to the man throughout his literary life, so it’s entirely possible that Shaw was in his mind to some extent, whilst writing that last book.

[9] The other reference is to Moore’s famous poem The Meeting of the Waters, celebrating the coming together of two rivers: the Avonmore and the Avonbeg – in Irish Abhainn Mhór and Abhainn Bheag meaning, respectively Big River and Small River – at a spot called the Meeting of the Waters in the Vale of Avoca in Wicklow, to form the Avoca River (whose etymology is entirely different, being derived from the Oboka, which appears in Ptolemy’s The Geography – don’t ask me why, I just look this stuff up). Anyway, a small sample shows what Joyce was playing off:

There is not in this wide world a valley so sweet

As that vale in whose bosom the bright waters meet!

Oh the last rays of feeling and life must depart

Ere the bloom of that valley shall fade from my heart

[10] Thomas Moore was responsible, along with British publisher John Murray, burning Lord Byron’s memoirs after his death in Missolonghi, trying to take Lepanto. Murray later gave Moore nearly £5,000 to write a life of Byron. Not that I’d be suggesting there was anything amiss or underhand going on, you understand.

[11] As Joyce would have it, at the start of Finnegans Wake.

[12] – The Deanes, along with Benjamin Woodward, were also responsible for the Kildare Street Club, now the Alliance Française building, back down where Kildare Street abuts onto Nassau Street, whose stone carved window frames feature billiards-playing monkeys.

[13] Professor Anthony Roche, retired Joycean scholar, and publisher in 1966 of Merry Marvel Fanzine, the first comics fanzine on this side of the Atlantic; Dr Maebh Long, author of Assembling Flann O’Brien, and editor of the forthcoming The Collected Letters of Flann O’Brien, much anticipated by this writer; Jack Fennell, author of Irish Science Fiction, and editor of the forthcoming A Brilliant Void: A Selection of Classic Irish Science Fiction, also much anticipated; and, last but by no means least, James Bacon, author of more fan writing than you could shake a big stick at.

Additional reading:

The closure of public lavatories in Dublin: http://www.thejournal.ie/public-toilets-dublin-755462-Jan2013/

The destruction of a public lavatory for the Luas line: http://www.thejournal.ie/public-toilet-site-demolished-luas-works-2747693-May2016/