Exploring Dublin’s Live Literary Scene

I hesitate to romanticize being Irish, or Ireland in general. It is a place; people live here. Occasionally we get things right, often we get them wrong. Some things are improving. Others aren’t. It rains.

One thing Ireland is particularly known for is being a nation of ‘writers and storytellers,’ which does sound extremely impressive, especially on a tourism brochure. Unlike a lot of preconceptions about Ireland, this has the benefit of being true. We buy a lot of books here. We fiercely defend indie bookstores. Despite the recent recession, more and more literary festivals are popping up each year like flowers after rain. It is completely normal, at a large family gathering, for that nine-foot tall lumpen uncle who spends three hundred and sixty-four days of the year communicating solely in frowns (every Irish family has one of these) to suddenly stand and recite a fifteen-minute-long poem from memory.

When I visit a school to talk about books, I don’t like to put anyone on the spot by asking who wants to be a writer, but I’ve visited schools where every single student puts up their hands. Teachers tell me with pride that ‘some schools are rugby schools and other schools are football schools, this is a writing school.’

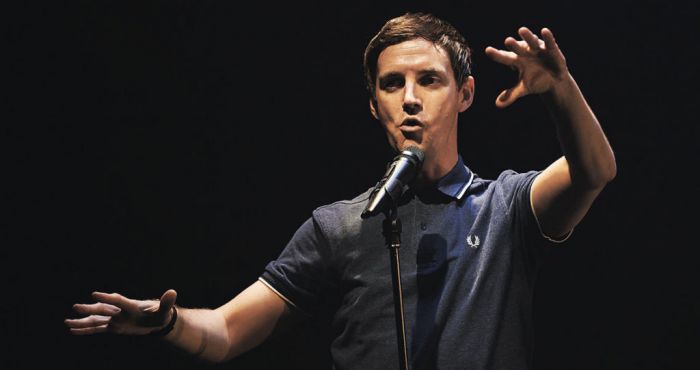

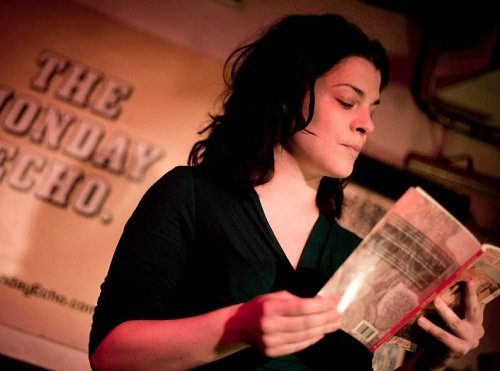

And nowhere is this passion for storytelling clearer than Dublin. Writers like Joyce, O’Brien and Swift loom large, of course, but they are a bedrock, a fertile soil for a living, vibrant ecosystem. When I first moved to Dublin, it seemed that every single pub had its own spoken word night. There was Nighthawks in the Cobalt Café, Brown Bread Mixtape in the Stag’s Head, Milk & Cookies Storytelling in the Exchange. The International Bar has a different event on every night of the week, from the Monday Echo to Playtyme to the Underground Beat. And in all these places there was an unseen compact particular to storytelling and spoken word – the audience were on your side. Nobody heckled or tried to throw you off-balance. They wanted you to succeed.

The comedian Hannah Gadsby, in her sublime Netflix special Nanette, described comedy as ‘trauma and punchline,’ whereas storytelling, in contrast, offers more by being made of ‘beginning, middle and end.’ Storytelling isn’t a binary art. In comedy, if the audience aren’t laughing you aren’t doing your job. Storytelling offered more options – from the sweet to the sad to the scary.

Of course, you can only rely on the audience’s charity so far. The first time I told a story in public, it was an unmitigated disaster. I had written a short story about a father who, every night, brought dinner in bed to his daughter. He would lay everything out perfectly on a tray and tell her a story about how she was going to grow up and become a princess, or a pirate, or a poet. She knew that he was lying. She knew, and the reader knew too, from the machines and tubes and soft ragged beeps crowding the corners of her room, that it was unlikely that she would grow up at all. But it was the performance that was important, for both.

I decided to tell this story at an open-mic storytelling night called Milk & Cookies. There were two things I didn’t know. The first was what the etiquette was after finishing the story. Did I bow? Was that too formal? Did I just leave the stage? The second was that the nights were themed, and unbeknownst to me, the theme of this night was truth or false, where the audience would cheer if they thought the story was true, and boo if they thought it was false.

I arrived, signed up, listened to stories about old gods and bad break-ups, and then my turn arrived. I was incredibly nervous – the kind of nerves that can only come from meeting the gaze of fifty expectant faces. I stammered through my story (a story written in first-person; this is important) eyes for the most part on the floor, and when I finished…

Silence.

A long silence.

And then a girl at the front whispered, ‘Oh my god.’

Not knowing what to do, I ran back to my seat. The MC shuffled back on stage, looking as awkward as I felt, and said ‘Oh. Oh dude. Um. Obviously, we’re not going to ask you if that’s true or not. We’re so… so sorry.’

Which is when I realized all of them thought that my nerves were sadness, and my story was true. I immediately apologized profusely, and the tension in the air escaped like air from a balloon. That was the moment I learned that, far from being scary or judgemental or disinterested, audiences want to trust a performer or author. They give you that gift – you just have to make sure you don’t screw it up.

The spoken word scene here is still vibrant – full of veteran performers and new talents taking their first steps onto the stage. The International Bar is a must, as is the Poetry Ireland list of open mic opportunities. Sometimes clichés are there for a reason. There is a vein of story in Ireland, rich and beating beneath our skin, and if you’re travelling here for Worldcon, or just passing through in general, it’s a vein you should seek out. Maybe you’ll decide you want to tell a story yourself.

Just maybe check is the night themed first.

Dave Rudden is the author of the award-winning Knights of the Borrowed Dark trilogy and the Doctor Who anthology Twelve Angels Weeping. He enjoys cats, good beard maintenance and being cruel to fictional teenagers. Follow him at @d_ruddenwrites.

Dave Rudden is the author of the award-winning Knights of the Borrowed Dark trilogy and the Doctor Who anthology Twelve Angels Weeping. He enjoys cats, good beard maintenance and being cruel to fictional teenagers. Follow him at @d_ruddenwrites.