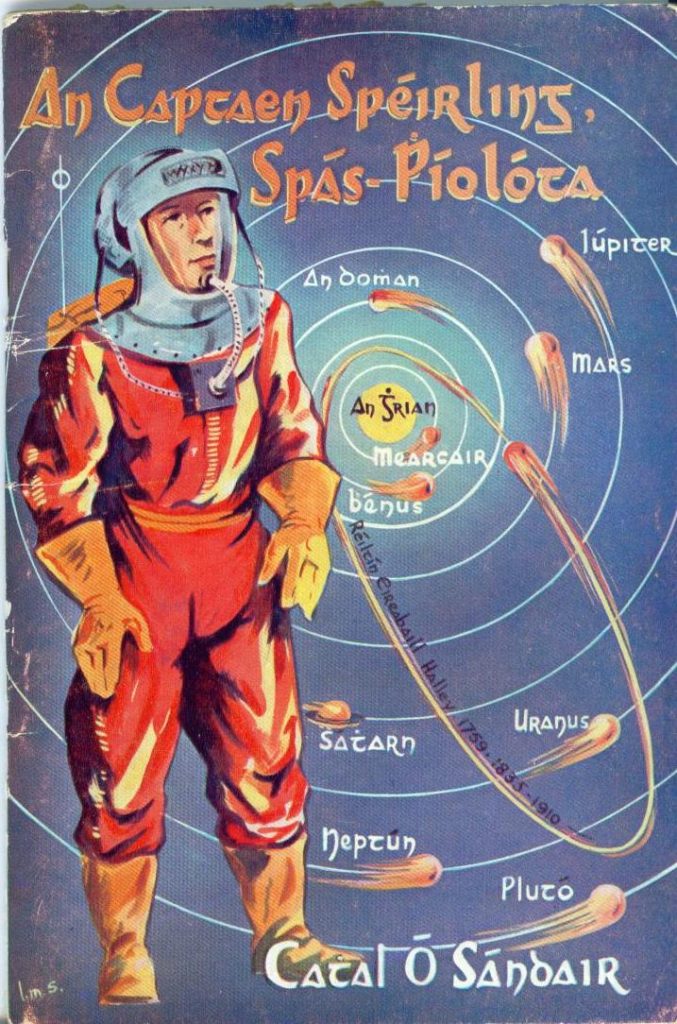

We have a fantastic surprise for you! Last year, author Jack Fennell contacted us and offered to support the Dublin 2019 Worldcon Bid with a brilliant gift. He’s allowed us to publish his bibliography of Irish Science Fiction, which describes hundreds Irish Science Fiction stories and books published from the 1850s to the present day. We’ve launched the pdf. of this below and will have printed copies available on our tables at conventions around the world. It’s a fascinating read, taking us from political utopias to young adult flights of fancy. Many of the works cited are, or will be part of our Irish Fiction Friday series. Below, Jack tells us how his original book Irish Science Fiction came to pass, and he offers some kind words for the bid.

Download A Short Guide to Irish Science Fiction by clicking this link. If you need a pdf reader, you can find one here.

The Blob McCabe

Jack Fennell

For many people, the idea of Irish science fiction seems ridiculous. It conjures up images of science fiction tropes injected violently into the rural Irish landscape, and vice-versa, the rural Irish clumsily inserted into a science fiction milieu. The former is illustrated in this joke, set in County Clare:

A farmer is sitting on a stone wall near Quilty, taking a cigarette break on his walk home from the fields. As he sits there smoking, he hears a strange humming noise overhead. He looks up, and to his amazement he sees a flying saucer. The flying saucer lands in the middle of the boreen in front of him. A door opens and a ramp extends. Down this ramp waddle three little grey men, with huge heads and black compound eyes. The farmer is frozen to the spot in sheer terror.

The leader of the alien trio waddles up to the farmer and says, “C’mere to me, are you local are you?”

“Yeah, I am,” the farmer answers, his jaw hanging open.

“Tell me,” the alien leader continues, “are all the Maguire girls married?”

The farmer thinks about this for a second, completely thrown by the question. Eventually, he responds, “Aye, they are.”

Dejected, the alien leader turns to his comrades and says, “C’mon so, lads. We’d best be goin’ home, we have no business here.”

To appreciate the joke to its full effect, you have to imagine the alien’s lines delivered in a Wesht Clare brogue.

The other comic cluster of images, that of the Irish in an SF story, has many examples. The satirical television show Nighthawks broadcasted a regular series of sketches called “Cork People in Space.” Another example is Brendan Grace’s yarn about the Irish astronauts (who call themselves ‘Spacers’), preparing to blast off into space from the Curragh in a turf-powered rocket. Not only is the idea of Irish people in space thought to be essentially comedic, but the very thought of Irish people attempting to do so provokes laughter—mainly, it must be said, from Irish audiences.

While this comic attitude is personally very annoying to me, I have to admit that my own perspective stems from a comic misunderstanding.

When I was still in primary school, about the age of seven or eight, an idealistic teacher advised us to watch Jim Sheridan’s film adaptation of John B. Keane’s play The Field, perhaps hoping to instil the young minds of the class with an awareness of our literary heritage. The film was to be broadcast on television that night, and there would be a discussion of it in class the next day.

That night, I started watching The Field. At some point, I must have fallen asleep, and my bored-to-tears babysitter took advantage of my nap to switch the channel. On the other side was Chuck Russell’s 1988 remake of The Blob. When I awoke, I was somewhat startled at the abrupt shift in tone, but in my dozy state, I believed I was still watching The Field. The mish-mashed narrative made sense to me: the reason that the Bull McCabe and the American were fighting over the field in question was because there was an alien blob living in it. And who wouldn’t want a blob of their very own? My eight-year-old mind could come up with all kinds of practical uses for such a creature, provided it was properly trained.

I was hugely disappointed to realise my mistake the next day. In my mind, possession of the blob was a much more compelling motive for the conflict than land ownership, and to this day, the two films are inextricably linked in my mind. Consequently, I grew up not understanding why the combination of Ireland with science fiction was so ridiculous. The stitched-together imagery in my imagination led me to understand that rural Ireland was just as suited to science fiction as any other setting. Despite what has been the norm for sf films throughout the decades, I knew that if aliens did decide to invade Earth, their activities would not just be confined to North America. Planetary conquest logically means that all nations are fair game, and Ireland would be a choice location for a first strike, since we could not retaliate with nuclear weaponry.

When I started my doctoral research into Irish SF, I thought that I had picked a nice handy topic: there couldn’t be that many Irish SF novels and short stories out there, and whatever amount there was must be very recent. Over the course of the next four years, I was proven wrong over and over again. There were hundreds of texts out there, so many that I had to abandon my plans to write a comprehensive overview. What struck me as particularly bizarre, though, was the difficulty I had in finding this stuff when there was such an abundance of it. The reasons became apparent as I continued digging.

Firstly, it was just an accepted truism that Ireland was not science-fictional. The phrase ‘Irish science fiction’ would, at best, bring forth memories of irascible Irish engineer Miles O’Brien from the Star Trek franchise (to date, the only character to shout “Bollocks!” on a Star Trek episode); at worst, it would trigger traumatic flashbacks to Leprechaun 4: In Space. The idea of Irish SF in itself was somewhat ridiculous, and more often than not played for laughs. There was a general perception, among the ‘uninitiated’ anyway, that the Irish just didn’t bother imagining such things.

This idea is, as we surely know by now, utter codswallop. This WorldCon bid alone should be evidence enough of that, never mind the multiple national conventions, clubs, societies, websites and dedicated publishers devoted to SF, Fantasy and Horror. This bogus preconception can probably be traced back to time immemorial, but its most recent incarnation is undoubtedly a product of the 19th century, when economic mismanagement turned the country into a financial black hole. In addition to famine and mass depopulation, Ireland suffered a ‘brain drain’ as imaginative scientists, inventors and engineers moved to countries with better-funded research infrastructures: Ernest Walton was born in Waterford and graduated from Trinity College Dublin, but he had to move to Cambridge before he could become the first person to split an atom; Louis Brennan, originally from Castlebar in Mayo, invented the unmanned helicopter in Australia; and James J. Wood, an inventor with over 240 patents to his name, might never have realised his potential had his parents not emigrated to Connecticut from Kinsale when he was a child.

Secondly, SF was not considered ‘literature’ by people who should really have known better. This is nothing new, of course, but it was disheartening to see the Irish literati fall into that trap as well. Crime writer John Connolly once described how, after his first novel was published, he found himself looked down upon by the self-appointed gatekeepers of Ireland’s literary reputation: as he puts it, he was basically told, “Come back to us when you’ve written your Famine novel.” The end result was that Connolly no longer lives, works or sets any of his work in Ireland. Until very recently, Irish SF was seen to be just as sub-literary as its international counterparts, something worthy of a dismissive footnote at most, or occasionally a whimsical, patronising article.

Unlike the solipsistic suburban guff that informs a great deal of Anglo-American ‘high art’ literature, which is at least somewhat organic, I’m convinced that in Ireland, this avoidance of genre is all about keeping up with the Joneses. Our literary history is full of the fantastic: this is where Gulliver’s Travels, The Picture of Dorian Gray and Dracula came from, not to mention the old heroic sagas and vision-poetry. Rather than celebrate that mad box of tricks, however, many Irish people tried to distance themselves from it, especially in the early years of independence; there was a fear that indulging in non-realist material would amount to playing up to dreamy fairy-story stereotype, and we were keen to show that we could be as responsible and grown-up and rational as any other modern nation. Fantastic and science-fictional stuff was still published of course, but it was ignored and downplayed, largely for fear of what the neighbours might think.

So, the idea that the Irish just ‘didn’t do science’ was due to the lack of adequate research and education infrastructures in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the notion that we just ‘didn’t do SF’ was down to the fact that there wasn’t a cultural/critical infrastructure of writers and scholars prepared to take the genre seriously. The first gap was eventually filled over the course of the twentieth century, though its legacy of anti-modern culchie stereotypes still remains. The second gap lingered, however, so that ‘serious’ Irish writers were allowed to be neither modern nor pre-modern: you can’t do science, and you mustn’t do magic, so what does that leave you?

This is where conventions, small presses, societies, zines and the like became very important, because they constitute a different kind of infrastructure. Fandom is its own unique kind of infrastructure, converting raw enthusiasm into tangible things: every SF creator starts off as a fan, after all. Irish fandom (which in many cases took the form of self-conscious ‘guilty pleasures,’ only acknowledged in the presence of a fellow-traveller) was what allowed me to identify and track down all the material I never knew existed. The only way to find it, in many cases, was through word-of-mouth. Everyone I spoke to knew of one or two Irish SF books, and assumed that was all there was, but everyone had two different examples.

Things have changed an awful lot, of course, even in the past five or six years. SF fandom generally has joined mainstream culture (or been appropriated by it, depending on your point of view); lauded authors who once tried to distance themselves from the genre, even as they incorporated SF imagery into their works, have copped themselves on and now admit their own fan status; and a huge portion of ‘respectable’ film and TV drama is now inflected with SF, fantasy and horror. The cultural infrastructures are there now, and more are springing up every day.

If I don’t call a halt to this post I’ll keep bloviating until I use up all the site’s bandwidth, so I’ll end it here on this note: an Irish WorldCon would be a million shades of awesome, and I’m immensely proud to be contributing to the bid in this small way. See you all in Dublin in 2019.

Jack Fennell is the author of Irish Science Fiction. We would like to thank Jack for the huge amount of work he put into this project, as well as Lisa Macklem, Esther MacCallum-Stewart and Emma England for their work in bringing this to press.