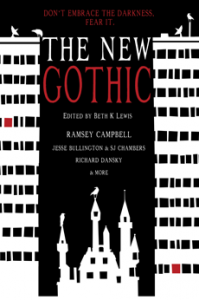

Are you ready for some horror? Today’s Irish Fiction Friday brings you “The Whipping Boy” by Damien Kelly, an exclusive tale of horror that was originally published in The New Gothic and made available to the Dublin2019 blog courtesy of Stone Skin Press.

Are you ready for some horror? Today’s Irish Fiction Friday brings you “The Whipping Boy” by Damien Kelly, an exclusive tale of horror that was originally published in The New Gothic and made available to the Dublin2019 blog courtesy of Stone Skin Press.

The Gothic is the most enduring literary tradition in history but in recent years friendly ghosts and vegetarian vampires threaten its foundations. The New Gothic is a collection of short stories which revisits to the core archetypes of the Gothic, the rambling, secret-filled building, the stranger seeking answers, the black-hearted tyrant, and reminds us not to embrace but to fear the darkness. A dozen tales of terror fill this anthology including an original, never-before-seen story from the godfather of modern horror, Ramsey Campbell.

Damien Kelly is a writer and psychology lecturer living in the untamed wilderness of the northwest of Ireland. He’s married to a beautiful pathologist and has two precocious children to fret over. The horror practically writes itself. Season of the Macabre, a collection of winter chillers, is published by Monico, an imprint of Clarion Publishing. You can find him online at damosays.com.

~

The Whipping Boy

by Damien Kelly

There was no water in the outside toilet. A brick cubicle on the far side of the yard, it held nothing more than a bucket with a seat, lined with old newspapers that you brought with you from the pile kept by the side of the kitchen range. That could stand a few visits, if all you needed was to piss. But if you shit in the bucket, you had to fold it up and carry it out to the gully to dump.

“Even in the night, Pius. Yours are so goddamned dirty. You leave a stink in there, and I find it? I will batter you.”

I knew he’d be on me later, kneading his fists in my guts, hoping to turn my bowels to soup and force me out to the bucket in the dark.

There was no water in the house. The chief reason for sending us to stay with our grandmother at Three Trees was so that we could do the walk up to the tap outside Swanton’s back door instead of her. It was what allowed her those three or four weeks residence in the summer, so she could still legitimately call it home. Two buckets of water, twice a day; one to drink from and one for the dishes in the sink.

Potatoes we could wash in the rain barrel, and did every day. Why were the Irish still in thrall to the potato? Even I, at ten years old, knew how the famine had happened. If it rained, you’d bring a basinful from the barrel into the long shed and wash the potatoes there. Crouching in the dust of decades-old turf, looking up at the swallows’ nests clinging to every corner, and listening to them squealing at you; stuttering chirrups, like machine-gun fire. It was the summers spent in Three Trees that taught me to think of birdsong as just so much startled screaming.

The long shed, the outside toilet, and the empty garage that my grandfather’s Morris Minor once sat in. They ranged about the main house, its grey face a chipped mess of pebble-dash mixed with crushed seashells, and lent it an illusion of stature. The tiny upstairs windows in the gable ends might appear reduced by distance, but, when sat by in the mid-dark of a summer’s night, they were revealed to be positively monastic, with all the attendant chill of a stone cell.

My grandmother cooked on a cast-iron range, turf burning, and that heated the kitchen, so we all stayed together in that one room, every evening. My mother had bought a television for the place; a brand new black and white portable, with push buttons for the stations instead of a dial. But the number of times we actually got reception on it I could have counted on the fingers of one hand. I think that, maybe more than anything, the boredom of those evenings was what made a monster of my cousin Shaun.

**

“Have you nothing to read, boys? Nor a pack of cards?”

I had Subbuteo in my case. I even had a pack of cards. But there wasn’t anyone to play with. My younger brother, Leo, was ever content under the settee with his Dinky cars and a handful of stones from the yard to set in their way. Shaun and I would huddle on opposite sides of the room, though, him on a chair by the kitchen table, me on the floor in the doorway to the scullery, each brooding on the paint bubbling off the walls, and what would transpire between us when we went to bed. My grandmother would stew tea and reread the yellow newspapers that lit the stove and lined the toilet, and never seem to recognise the atmosphere around her.

“When you’re at the shop tomorrow, see if they sell packs of cards instead of comics. Them damn comics don’t last five minutes. Or I could give you a couple of prayer books. For poor sinners.”

We three shared the big room at the top of the house. The thinking was that our combined body heat would make it livable at night. It had been the girls’ room thirty years before; my mother and her two older sisters. The older girls had the big double bed, while my mother had a single cot in the eaves. Now Shaun and I were the elder pair, so we shared while Leo slept alone. Ironically, Leo would have loved to have swapped with me. He adored Shaun, trailed after him, desperate to show the big boy whatever smooth stone or black, scuttling thing he’d just lifted off the ground. Shaun was all patience with Leo, you see, knowing how it stung me. But in this one thing, Leo was firmly denied. Shaun needed his entertainment, and wouldn’t let us switch beds.

“Hurts even if I just squeeze them, Pius. If I squeezed them hard, you could die.”

There was another room across from ours that had been my grandparents’, but my grandmother no longer used it. It stood above the sitting room and was warmed in the past by the fire that would have been lit there—but the sitting room door wasn’t even opened in all the weeks we spent there, let alone a second fire lit. My grandmother slept in the downstairs room my uncles had occupied, next to the kitchen and only half as deathly cold as a result.

Sometimes, I could slip out when Shaun was asleep, into the damp, empty bedroom across the hall and away from tattered dolls with painted eyes, the smell of the piss pot under the bed, and Shaun’s arms. Shaun’s legs. His sharp, unwelcome fingers, blunt, unstoppable knuckles, and the unknown hour when he’d wake. Of course, I was made to pay for flying the coop.

**

“What were you up the tree for anyway?”

“We were getting long sticks to make bows and arrows,” Leo answered when I wouldn’t.

“Suit you well enough to fall then. I’ll have to get a bit of butter to lift them wee stones out of the cut.”

“I didn’t fall.”

Of course I told. My parents and Shaun’s parents both would visit at the weekends, and I related every moment of the week’s torments with breathless urgency. But all Shaun had to do was tell the very same story to make none of it true. Leo would be standing there, emerging from behind Shaun’s leg like his very shadow, and the image of the little sadist I was trying to paint couldn’t have been more laughable. This was what childhood meant, I was told. This is what boyhood was. We were as bad as each other.

So I tried that.

**

It wasn’t hard to do. Shaun practically breathed malice and resentment; you couldn’t fail to breathe it in yourself if you shared the same air in the way we did. I watched him one morning, on the road below Swanton’s where it dipped into the gully it had been built across.

He was catching the hens he had chased down from their yard by the wings, and throwing them as high as he could. He was trying to get them over the high hedges of fuchsia and rhododendron, to dump them into the gully. Everyone used the gully as a rubbish tip; tossing over their bags of household refuse, or pushing their rusty bikes and broken furniture right through the hedge, to crash and buckle below. That was the bad end of the gully, but it wasn’t very much of it, and, for most of its length, it was clean and green, and dotted all along with natural springs. My granny talked all the time about how little it would take to tap them for the water we needed in the house, but nothing ever came of it.

I watched him then, the exultation of pure violence, and I could absolutely relate to what he was doing. So I ran, to join in, and he didn’t raise one word of objection.

The chickens were used to being handled and didn’t even try to evade us. A wing in each hand, bend your knees and flip them upwards. We never really had a hope of getting them the height of the hedge, but I could feel in my hands that it wasn’t about that. It was the feeling of separation in those stick-like bones, the click you could feel under your fingers as the wing was stretched beyond where it was meant to. Knowing for sure that you were hurting something that couldn’t tell you so, that was the thrill of the thing. This was the sensation Shaun had learned to tap into, to keep him interested long after I thought I’d stopped giving him the satisfaction of hearing me cry.

And that should have said something to me, it should have made me empathise with the stupid fucking bird in my hand, but I was thinking—I was always thinking—

I’m playing with Shaun. Shaun’s playing with me.

“What the hell are you at?”

Billy Swanton farmed the land next to my grandmother’s now that his father was retired, though he no longer lived with his parents at the house. He came up from his own place in the village at the Point, going back and forth between the two over the course of the day. You could hear him coming in the old tractor, but his first and last trips were always in the car, a new Datsun Bluebird, which was harder to hear. He’d spotted us from far up the road.

The first thing he did when he got out of the car was to lift the two buckets from the side of the road and tip them out.

“Now, get you pair of bastards back up that road and tell my mother and father what you were doing, or you can go back to your granny’s and tell her why there’ll be no water today.”

Shaun was blank faced and silent, but his fingers worked like he was tearing at some invisible cloth. He only shot me one glance on the way back up the lane, but it made clear that our moment of shared sensation had been an aberration. It was obviously my involvement which had gotten him caught.

I’ll make you pay, Pius, that one glance told me. Somehow. And soon.

And then old Laurie Swanton handed him the means.

**

The Swantons’ home had started out looking like Three Trees, but it had been radically remodeled over the years; now it was a split-level affair that looked like a bungalow from the side facing the road, but had a sitting room and bedrooms below, where the fields to the front sloped down to a cliff’s edge and the sea.

Billy’s mother, Maggie, was in the kitchen when we walked in. It was a bright room, quite unlike the kitchen we’d come from on the other side of the gully. Yellow Formica and yellow wallpaper, all reflected by the stainless steel draining board up onto Maggie’s soft face, where she stood peeling potatoes. The kitchen window in front of her was wide and looked onto the road—she couldn’t have failed to see Shaun taking the hens in the first place.

“Are you that bored?” she asked us, dryly. “My God, you wouldn’t be bored if your grandfather was still living. He’d have found plenty to keep you busy.”

Maggie Swanton was a nice woman. In her late sixties, neat and brown skinned, she couldn’t muster the volume or the edge to truly scold. But then, she wasn’t the person we had to answer to. Old Laurie Swanton, Billy’s father, was somewhere downstairs. We never saw him usually, nor heard his voice coming from the house in the way we’d hear Maggie or Billy when up filling the buckets. Until now, we’d only really known him by Billy’s frequent warnings about the man.

“My father will flay you alive if he sees any of you in that front field.”

“My father will take his whip to you, now, if that tap isn’t shut off properly when you’re done.”

“Do you see all those whips in the cattle byre? Those are my father’s; he makes them. See if any of you set one foot inside those doors, he’ll show you what he makes them for.”

True enough, the walls of Swanton’s cowsheds were hung all about with Laurie’s whips. I hated them. My father had taken me to the picture house a couple years previously to see Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter, and I was ever after haunted by the murder of the town marshal. You don’t shoot an unarmed man, so he was whipped to death instead by gunslingers—Bridges and the Carlin Boys—while the townsfolk of Lago, all in shadow, looked on. Laurie Swanton’s whips were not like the bullwhips in the westerns, though. The whips on the byre walls had long wooden handles, some three feet or even longer. The leather thongs had been knotted rather than woven, long and thin. They were more like the devices you’d see in the hands of Victorian coachmen, designed for reach and height. Somehow that only made them seem more frightening than the bullwhips that had done for the marshal.

He was making one when we descended to the sitting room. He made us sit together in one armchair while he sat across from us in his, perched on the cushion’s edge, holding a long strap close to the fire and knotting it while it was supple. My heart was in my mouth. I’d often had six on each hand from the Christian Brothers at school, and my daddy cut a willow switch that hurt far worse than the bamboo cane, but the knotted whip looked like it could actually slice through skin.

“Yes, but why were you throwing them? What pleasure is there in that?”

We neither of us had an answer. Or we did, but none that we would admit to.

He just wanted to scare the hens. I just wanted to be his friend.

Or—

He gets his kicks causing pain, and I didn’t want it to be to me.

Or—

He likes to hurt things. And I could like it too.

More than anything, though, I worried that if we didn’t soon say something, Laurie Swanton was like to ring it out of us. Wrap that whip around our throats and—

“We…thought we could get them to fly. A bit.”

Shaun took my meagre offering and was quick to embroider it.

“And we were seeing who was strong enough to get them really high, to make them fly for longer.”

Old Laurie didn’t look old. He was still lithe, and though his face was lined, it wasn’t jowly. The muscles in his forearms swelled and stretched as he worked the leather, like thick mooring ropes, coiling and pulling taut against a rocking tide of movement. He had the firelight in his eyes, and it coloured his skin as the walls of the kitchen had coloured Maggie’s; each painted by their natural habitat, like camouflage.

“That’s no test of strength,” Laurie said.

The last knot pulled tight, he wrapped the tail end of the leather strip over a razor and cut it away. Then he reached down to a glowing coal and—quickly, but not as quick as I thought he would—pressed the cut tip to it, scorching and sealing the frays.

Laurie lifted the handle and extended it to Shaun.

“That’ll test your hands and arms both, if you can get it to crack.”

“Is that for me? To keep?”

“Aye. You use the big long handle to tap the cattle and turn them, like a rider’s crop, but then the whip will reach to the front of the animal if you’re stuck behind it. Takes a whole lot more strength to crack that, than it does them ones the cowboys use, though.”

Shaun raised and flicked his new toy; hesitantly, experimentally.

“Not in here, now. Go and ask Billy to show you how to crack it. Pius, you sit there a minute, and I’ll get another one for you.”

Laurie rose, and Shaun rose with him, jogging to the stairs with a—

“Thank you.”

—that rang with the relief he no doubt felt at not being on the receiving end of his new whip. So buoyed, he almost forgot to look back. Then, halfway up, he glanced at me a second time.

Somehow and soon, Pius. I told you.

A shaft of wood tapped my knee and was laid across my lap.

Shaun’s whip hadn’t seemed as big. If this one was—as it appeared to be—bigger than his, it’d only provoke him further.

And you don’t shoot an unarmed man, the cowboys said.

“No, thank you.”

Laurie came round to face me, and I held it up. He really wasn’t very old.

“You’re the whipping boy then, are you?”

“No—I don’t want it.”

“The whipping boy gets whipped, son; he doesn’t dish it out.”

He retook his seat, leaning to scoop another log onto the fire. It wasn’t cold, inside or out. It wasn’t too hot though, either.

“The whipping boy took the beating for someone else. His greaters, if not betters.” He sank back into the chair and only then did the seeming of a great age wrap about him, in a way I’d not perceived when he was standing. “Is that what the other fella is to you?”

I set the whip back onto my knee. I had the sense that this was the opening to a conversation I’d been trying to have for weeks, but I had no idea how to have it with this stranger neighbour.

“No.”

“He does wrong, you suffer the consequences. No?”

“Not—not from other people.”

“Really? I hear you’re as bad as each other.”

For a second my fingers were moving, looking for that feeling of wing bones pulled beyond their limits. Instead they found the knobby surface of the whip’s handle.

“That’s oak, from some of them big trees your side of the gully. His is only birch, much lighter. His has more spring, but yours won’t break. It’ll take more strength to get a crack out of that, though, the weight of it. But I think you want to carry more weight. Still, if you can crack yours, you’re stronger than him.”

I gripped it properly then, and stood.

“Thank you.”

“I know, Pius, how it feels to be tarred the villain by someone else’s brush. The only way to escape it is to stop taking the whip, and start carrying it instead. Show him you’re his equal, and that you’re not interested in playing his games anymore.”

Shaun was at the byre door when I got back outside, Billy handing him back the birch-handled whip. It swished with a fine whistle when Shaun flicked it out before him, and, though it didn’t crack, the impression that it could slice through flesh had diminished none. He positively grinned at me as the tip touched ground and all the fine gravel spun away, in puffs of dust like gun smoke.

I could see the standoff to come, where my whip would only help to substantiate his version of events in the inevitable aftermath. I might be the one crying, but we would be as bad as each other.

But I knew he was worse—

Show him you’re his equal.

—so I needed to do worse.

I crossed the yard to where he and Billy were standing. I couldn’t make it crack any more than he could, but my whip weighed more than his, and I was stronger than him.

It was the wooden tip of the handle that ripped through his cheek, not the leather knots.

Shaun was screaming his teeth out, Billy roaring at me like a bull. Maggie came squealing up behind me from the house. The blood had been a flash going off—like a camera bulb—now just an after-image in my swimming vision.

I had nowhere to run. But I ran. And ended up back down the stairs in front of Laurie.

As I held the whip out, trying to give it back for a second time, we both saw how much blood was on it.

“I—”

He looked so confused. “No.”

Whatever else he’d meant to say got lost in that moment. Instead he looked up, right at the ceiling, and his jaw worked like it was on the end of a broken spring. When he looked down, his ruddy face had turned ashen.

“Ah, Pius.” He took the whip and wiped the end of the handle through his fist. It came away clean. “You weren’t—I never meant you to go that far.”

I howled in panic, and my legs bent of their own accord. He stooped to steady me, his rope-like arms anchoring my body.

“What am I going to do?”

“It’s alright, I’ll sort it. You run home. Tell your granny that Billy is bringing the water.”

He ushered me to the stairs, and I staggered up to the kitchen door, my bladder threatening to empty with every step. I could see Billy standing over Shaun; my cousin had his back turned to me, so I couldn’t see his ruined face. Billy spotted me standing there and frowned. I wondered where his mother had gone—was she already on her way to granny?

“You’re in the bad books.”

Her voice startled me. Maggie was standing to my left; in her kitchen, still peeling potatoes, her soft face yellow.

“You may go out and face the music.”

“You could have had his eye out!” Billy snapped at me as I stepped outside.

Shaun turned round to look at me. His face was fine. There wasn’t a mark on it, though the blank expression—truly blank, not just well composed—was new. Billy and Maggie might not seem to remember what had happened only minutes before, but it looked like Shaun did.

“Away home, you. Shaun and I can bring the water.”

When they eventually reached Three Trees, Billy was carrying the oak-handled whip.

“My father said to give it back to you—but see that you have a bit more care with it.”

Shaun stayed outside the rest of the evening, apart from ten minutes spent bolting his dinner at the table and avoiding my gaze. I stayed in, avoiding his.

I didn’t try telling myself that I’d imagined it, that it was just a morbid daydream. I had no alternative explanations, though. By day’s end I’d resolved to believe that God had somehow intervened; that—like Abraham—I was good, but had been on the cusp of doing something terrible. I had been given a second chance. I couldn’t decide if Laurie Swanton was an angel or just the tool to hand that God had used to teach me this lesson. I just had to hope that this meant things were going to get better.

I still couldn’t face Shaun, though.

That night, just as we were heading for the stairs, I complained of a belly cramp, grabbed a newspaper from the pile and took off for the toilet. I sat long enough that granny came looking for me, but I told her it was easing. Then I sat in the dark until the feeling had gone from my legs, such that they wouldn’t hold me, and I crawled back to the house on my knees. I lay on the front step until the pins and needles had passed, and when I finally went inside, granny was in bed. I treaded carefully on the stairs, and stopped short of the big room, opened my grandparents’ old room instead and headed to the damp bed there.

Shaun had been waiting behind the door. With his whip.

**

“Can you not stay in until you’ve had some breakfast at least? And why do you have a scarf on you? Pius? Pius!”

I didn’t take the road. I didn’t want to risk running into Billy Swanton before I could get to his father. I ran past the toilet and pushed through the fence, into the long fields that ran down from the yard towards the cliffs and the bay below. My grandmother rented them out for grazing, and the cattle began to turn and follow me as I ran down the side of the field, thinking I was there to lead them. I left them behind me quickly, ducking into the treeline that bordered the gully and down into the dark.

It might have been a river once, the many springs that rose along its length seeded by ancient waters rushing to fall from the cliffs. But the road had cut its throat, and the long bed was dry now. I planned to cross into the Swantons’ land and up to the sitting room window, hoping to spot Laurie in his seat by the fire. Failing that, see if I could find a way in other than the kitchen door, as I didn’t have anything more to say to Maggie than I did to her son Billy. I needed Laurie. I had to believe that he was the angel I’d imagined him to be.

My guardian angel was waiting for me in the gully.

“What’s that scarf covering?”

I pulled the scarf away. There was no sense in being evasive anymore.

Broken vessels marked the points where each knot had dug in; a necklace of bloody pearls.

“With the whip I gave him?”

“Can you take it away? Please?”

He drew breath for a long time. I thought he would say something enormous, something biblical; something that needed an amount of air commensurate to its enormity. He must have changed his mind, though, and the how of my request remained unspoken.

“Why?”

The spring waters pattered on the stones, a fluttering heartbeat that echoed down the channel.

“I don’t want anyone to see.”

Laurie came across the gully to put his fingers on my neck. His hands were ruined by days working outside and nights working leather by the fire. They brushed my skin like hide gone dry.

“Why not show everyone what he’s done to you? Haven’t you been trying to tell them over and over?”

“But this was my fault. Because of what I did to him yesterday, before you fixed it. I am as bad as him now.”

“Is that what you believe?”

“Believe?”

I’d obviously been thinking about what I was supposed to have learned from Laurie’s actions the day before. I’d worked out that some test of faith was bound to be part of what was happening.

“I believe in God, I swear. And…I believe that everyone deserves to be forgiven. I do.”

Laurie hissed through his teeth.

“I don’t know what else I’m meant to say, I’m sorry. You’re my guardian angel, Mr. Swanton, and I believe in you.”

He continued to trace his fingers over my skin as I spoke. It didn’t feel like it was easing any.

I’d come to him, the moment I could. He’d been waiting—hell, he’d met me halfway. I had no idea what further part of the bargain I was failing to satisfy; all I could think about was the urgency of the situation.

“Please—if he tells on me, they’ll find out about you too.”

“That sounds like a threat, Pius.”

“No! I just meant that we’d be helping each other.”

His eyes were watery this close. Not tearful, but drowned; seeping on themselves like the rocks at our feet.

Laurie let go of my throat. It hadn’t healed. He turned and began to climb the slope on his own side of the gully, reaching up to the low-hanging branches to give himself balance.

“Please!”

“I’m not your guardian angel, son.”

“But—how did you know I was coming to look for you, then?”

“Because I’m the kind of angel that knows when somebody wants something, Pius, and what they’re willing to give up to get it.”

He gave me a look, all in shadow from the trees, and in my head I was suddenly back in the darkened picture house, watching Clint Eastwood play the Stranger from High Plains Drifter. Hand raised like Clint’s, painting over the sign for Lago and writing Hell in its place.

“Are you—?”

“Tell your granny, Pius.”

“Are you the Devil?”

Another enormous drink of air.

“I was.”

Such quiet. The springs stopped bubbling around us, and the only patter was of blood in the small organ of my fear. Then suddenly, they burst with bullets of steam. I yelped like a pup.

“I suppose,” said Laurie, “I still am.”

I ran again, away from him this time, though he’d shown no signs of turning back. I didn’t know whether to run for my granny and beg her for the prayer book, or to run straight to the village and try to find the priest.

As bad as Shaun? I was worse. I was going to Hell.

“Pius!”

I’d made it halfway back up the field, following the treeline of the gully, and Shaun was dropping down from the top of the gate that separated the yard from the fields.

“Shaun! Old Laurie Swanton is the Devil!”

“Did you tell?”

His question caught me short, and I stopped where I was. “What?”

“You’re not wearing your scarf. Did you tell old Laurie on me?”

He pushed away from the gate, and his hand came forward. He had the birch whip in it. He’d obviously been waiting for me a while, as the cattle had come to the head of the field to him. He tapped them with the whip handle to part the herd as he came towards me.

“Laurie is the Devil, Shaun. It was him fixed your face and took away all the blood, and I wanted him to—”

“What are you talking about? Stop talking shit—what did you tell him about your neck?”

Laurie had fixed more than I’d thought. I’d assumed the look on Shaun’s face the day before to be remembrance of the real course of events, but it seemed not. What had last night been about then?

“Shaun, I swear, Laurie Swanton is the Devil, and he gave us those whips to make us fight. He egged me on to cut your face—”

“I knew it. I knew that’s what you were trying to do, not crack the whip at all.”

For wanting to hurt him. Shaun had strangled me just for wanting to hurt him back.

And then he raised and snapped his own whip. It cracked like a gunshot, just as Billy must have showed him after I’d gone. A heifer to his right leapt in alarm, and the herd moved with her as she moved back out of his way.

“Did you tell on me, Pius?”

He’d been practising. He must have spent the whole evening outside doing nothing else. He passed the whip to his off hand and cracked on the other side. The cattle leapt in greater numbers. He was pushing them forward alongside him.

“He knew,” I shouted. “He’s the—”

Another crack, closely followed by one more to the far side, and the cattle were jogging now, moving ahead of him rather than just apace. Skittish, ready to run. At me.

“Not until you took your scarf off.”

And then, just as I had thrashed him in the face with the oak handle, Shaun swung his birch rod backhand with all his might, cracking it into the back of the closest cow. I had the trees behind me, and he knew if I ran that would only draw them on faster. He meant for them to plough me into the earth, to toss me into the gully with the rest of the rubbish.

The cow dropped her head, planted her front hooves, pulled up the back ones, and kicked him. He only took the one hoof to the chest, but she smashed him like a china doll.

I stood and watched him, bubbling like a crimson spring. Then he burst, like a head of steam — a red spray thrown high, as his neck and chest went into spasm. Then he stopped.

I felt the oak handle slide into my hand and turned to see Laurie beside me.

“Do you want me to fix it?”

I willed myself to answer; willed my dry mouth to move and say yes, change the world again. Bring Shaun back to life.

“Should I change what’s happened, Pius?”

But I couldn’t speak. I didn’t speak. The cattle had closed around me, and I raised the oak whip to urge them aside and send them down the field.

“Maybe just this, then,” the Devil said.

And as the cattle moved away, I could see my granny standing at the gate to the field, from where she had apparently observed it all.

“She doesn’t see me,” Laurie told me. “You and I are done now, Pius.”

“Am I going to Hell?”

“I don’t know. I don’t care. I never had anything to do with that. But you’re definitely a great one for choosing to be the victim, so I’m sure you’ll find a way down if that’s what you want.”

**

We came back again the following summer. Granny, Leo, and I, and this time my parents stayed too. Old Laurie Swanton was dead, we heard. Maggie didn’t seem too sad. She was a nice woman.

There was never any water in the house. Their gully springs ran dry the year Shaun died. It put pay to any plans of using them to bring water to the house, which in turn seemed to signal the end of granny going home to Three Trees. She took her first trip to Majorca with my uncle the following summer and died at Halloween.

But that final summer was glorious. They worked so hard to make different memories for me. My parents opened up the good sitting room and lit the fire there, which seemed to warm the whole upstairs and not just the smaller room where they slept. We played in the fields with our whips, and there was Subbuteo or a card school in the evenings, presuming there was no reception on the TV.

But at night I felt ashamed. The daylight joys were whips to scourge me in my dreams. Whips in Shaun’s hands.

I shared the bed with Leo now, and I would watch him sleeping when I couldn’t. Even the hiss of his breathing was like the whistle of a whip in the air, which only added to my frustration. In truth, it made me angry.

Sometimes, it made me so angry, I felt like cracking him.